The Curious Case of John Walker Lindh

How an American Teen Became a Modern Symbol of Mind Control

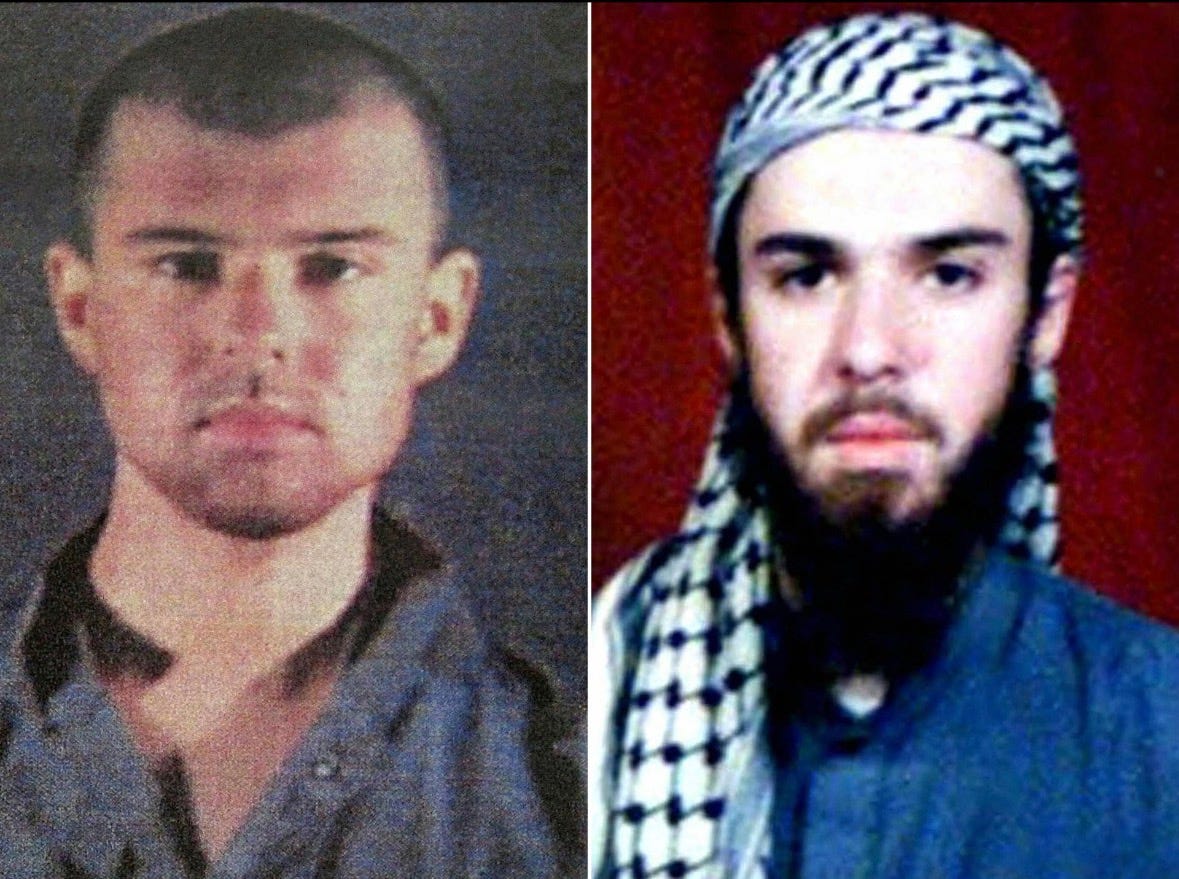

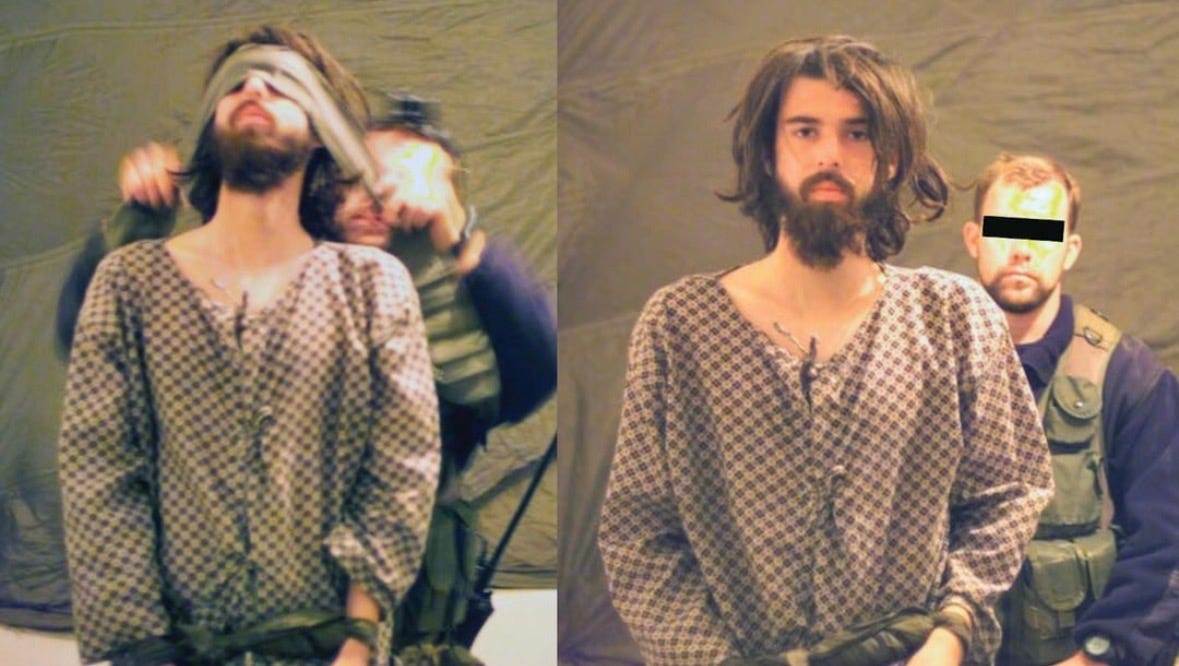

When John Walker Lindh was pulled, disoriented and frostbitten, from the desolate Afghan hillsides in late 2001, the world saw a villain. Americans called him the “American Taliban,” a traitor who had turned his back on his country in favor of a medieval theocracy. Yet, what lay beneath the headlines was a human riddle, or an almost clinical demonstration of how identity itself can be dissolved and rewritten under the right sequence of psychological pressures.

Lindh’s journey did not begin on a battlefield, but in a quiet, liberal suburb of Marin County, California. By all appearances, he was a bright, introspective boy, inclined toward language, poetry, and spiritual seeking. That seeking, and a restless hunger for meaning in a culture saturated with noise, made him, paradoxically, the perfect subject for an emergent form of soft radicalization that would later resemble, in structure and intent, the methodologies described in intelligence manuals and cult deprogramming case studies.

Brainwashing, though treated in popular culture as a Cold War relic or a cinematic cliché, is far from fictional. Psychological conditioning does not require electrodes or laboratory hypnosis. It thrives instead on isolation, deprivation, and the gradual reframing of a person’s moral landscape until old loyalties seem delusional and new ones feel like salvation. Lindh’s transformation was not a matter of overnight persuasion, but of a progressive erosion of psychological autonomy.

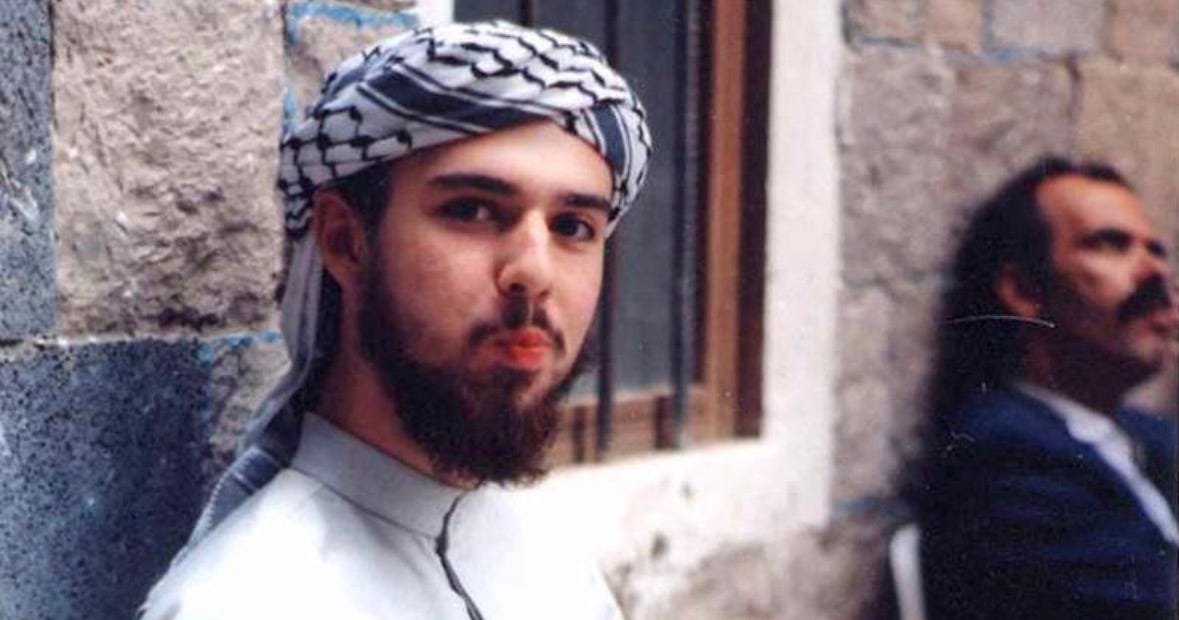

By the time he arrived in Yemen and later Pakistan to study Islam, Lindh had entered what psychologists might call a “totalistic environment.” It was a system in which every aspect of thought, routine, and language was controlled to channel the convert’s identity toward a single ideological endpoint. He was immersed in a linguistic and cultural cocoon where everything (ritual, cadence, dress, even vowel formation) reinforced a single narrative: Western corruption versus spiritual purity.

The accent he eventually acquired symbolized more than mimicry. It was the final grafting of an imposed linguistic rhythm onto the deeper architecture of his self. The tongue changed because the worldview did.

Such transformations follow a particular rhythm known to military and intelligence psychologists. Step one: establish controlled isolation, ensuring the subject’s only source of information and validation comes from the group. Step two: dismantle prior identity markers, language, nationality, moral relativism. Step three: replace the void with a purified ideal, usually expressed in the language of moral certainty and divine purpose.

This gradual collapse and reconstruction of the ego mirrors what prisoners of war endure in ideological “re-education” camps, or what trafficking survivors later describe as “falling under a spell.” It is persuasion stripped of reason and replaced by emotional entrapment.

What makes Lindh’s case especially poignant is that, unlike trained spies or soldiers subjected to known techniques, he sought transformation voluntarily. He was not captured and enslaved: he was absorbed. His radicalizers did not need whips or cages, only belonging, propaganda and coercive control techniques.

For a young man starving for transcendence, their conviction radiated like warmth. Every human mind, when deprived of belonging and meaning, develops a sort of sensory hunger. Indoctrinators feed that hunger in precise doses until the subject begins to believe that obedience itself is freedom.

When critics dismiss mind control as “pseudoscience,” they overlook how modern psychological operations, cult indoctrination, and ideological grooming draw from the same psychological blueprint. Deindividuation, dependence, cognitive dissonance, and identity realignment are not theories: they are operational techniques. They do not merely change what a person believes, they change who the person is allowed to be.

Lindh’s accent, mannerisms, and internal narrative, all became artifacts of a rewired consciousness.

In the aftermath, when Lindh was captured and displayed on television screens, public revulsion served as a convenient buffer against the deeper discomfort of recognition. His story doesn’t reflect a singular pathology, but a universal vulnerability: the mechanism by which any person, given enough loneliness and ideology, can become a vessel for someone else’s beliefs. Before he ever carried a rifle, Lindh had surrendered something far more sacred: his agency.

The tragedy doesn’t just lie in his choices, but in the moral convenience of those who framed them. Hatred was easier than comprehension. Yet, if we strip the politics away, what remains is an unsettling parable of psychic colonization.

The American Taliban was not born. He was manufactured through techniques perfected in war zones, intelligence facilities, and religious compounds alike. His accent, that uncanny echo of his handlers, was the audible residue of transformation, and the sound of a mind that had been retuned to a foreign frequency.

In that sense, John Walker Lindh was less a traitor than a test case, and a window into the fragility of individuality under the pressure of certainty. His life remains a cautionary mirror: that brainwashing is not about intelligence or willpower, but about the human need to belong, and how easily that need can be weaponized.

Know anyone who’s been brainwashed or indoctrinated into a cult? Familiar with how to spot the signs?